Drone Delivery

Researchers Ask: Can Delivery Drones Positively Impact Climate Change?

Researchers Ask: Can Delivery Drones Positively Impact Climate Change?

Each and every day drone delivery moves closer to reality – with major companies such as Amazon and Bell already developing solutions to replace truck delivery with drones, if not in entirety at least in part. But will these innovations ultimately amount to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions?

Researchers from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Carnegie Mellon University, SRI International and the University of Colorado–Boulder recently published the results of their research in Nature Magazine seeking to discover to whether drone delivery could reduce the need for heavy vehicles to perform the task entirely, reducing fuel use and carbon emissions, and thereby have a positive impact upon climate change.

It’s a pertinent question, and something delivery drone manufacturers already suspect. As Nathan Wrench of Cambridge Consultants told us last year, “Current methods for delivering goods in e-commerce suffer from efficiency problems – the last mile accounts for ~30% of the logistics cost, on average. That cost is also closely associated with the environmental burden of the logistics, from an emissions and congestion point of view. Moving the final mile delivery to very small, lightweight electric powered vehicles that can travel point-to-point avoiding traffic is a highly appealing idea, which is why it is gaining such attention.”

Delivair Lightweight Delivery Drone | Cambridge Consultants

The transition in the U.S. electricity sector to generating power with less greenhouse emissions is underway, but in the main transportation is still largely powered by fuels made from oil and remains the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions.

According to research, in the U.S. as much as one-quarter of transportation emissions, the equivalent of 415 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, and comes from medium and heavy duty trucks and other vehicles which deliver freight to warehouses, businesses and consumers’ homes.

In an article authored by the researchers in The Conversation, they stated that they began with the premise that reducing the need for trucking by delivering some packages with electric drones might save fuel, and potentially carbon emissions, the research team modeled how much energy drone delivery would use, and how it would be different from the ways packages are delivered now.

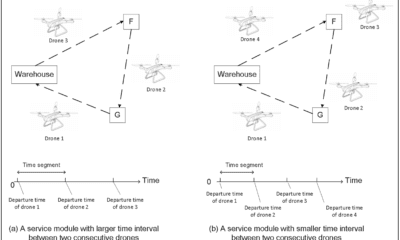

It’s known that the amount of energy a drone uses depends on how heavy the drone itself is, its batteries and whatever packages it’s carrying – as well as other factors, including how it’s speed and wind conditions. To address these anomalies, the researchers measured the energy used by quadcopter and octocopter-style drones while carrying different payloads. They also gauged whether that might change how the U.S. uses energy and if there would be any resulting environmental effects.

In order to glean a general estimate, they used a quadcopter drone capable of delivering a 1.1 pound (0.5 kg) package and an octocopter drone capable of delivering a 17.6 pound (8 kg) package, each with a range of about 2.5 miles (4 km); while they considered a range of battery technologies and fuels, they focused on lithium-based batteries for their base case, because most electric drones currently in use are powered this way.

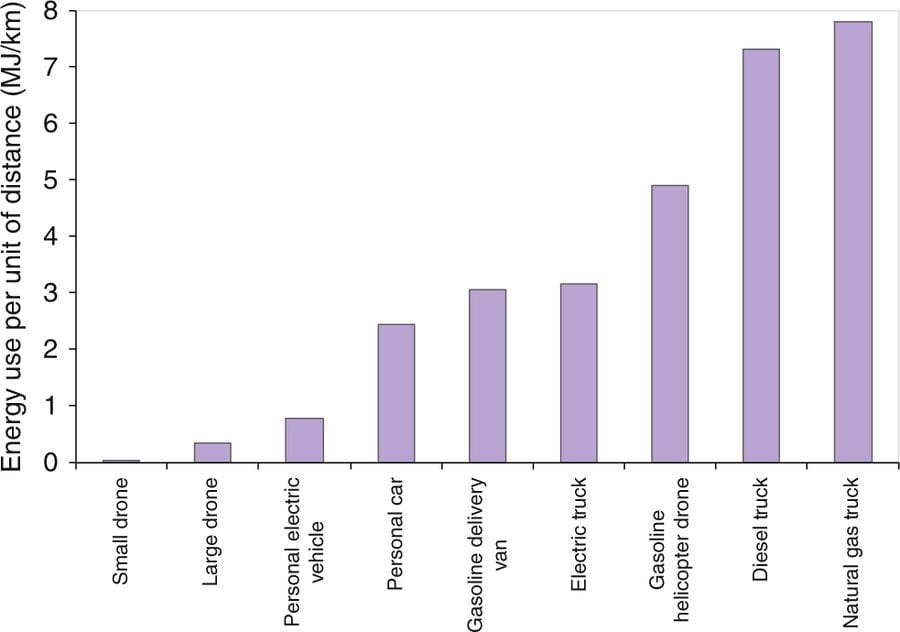

There were also differences in transport style and capabilities to be taken into account. For example, despite the fact that an electric drone is defying gravity to stay airborne, it uses much less energy per mile than a heavy steel delivery truck burning diesel fuel; however a delivery truck or van can carry many packages at once, hence energy needs and environmental effects were allocated per package.

In addition, due to the differing energy and emissions profiles of fuels used by delivery vehicles, researchers took into account the embedded energy requirements of making these fuels compared to producing electric UAV batteries. At present, the energy needed to transform crude oil into diesel fuel can add another 20 percent or more of greenhouse gases to the amount generated when the fuel is burned; and while the manufacture of batteries is improving, the process nevertheless still does generate carbon dioxide.

The team calculated the amount of greenhouse gases emitted and found burning a gallon of diesel fuel emits around 10kg of carbon dioxide, while emissions from electricity vary by region, depending on method of generation – ranging from burning natural gas and coal to generate power, to relying more heavily on sustainable sources of energy such as nuclear, hydropower, wind and solar power.

Energy required per km of travel for individual package delivery vehicles. | Credit: Nature.com

The researchers found that in some cases using electric-powered drones rather than diesel-powered vehicles could reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, but in other cases, using trucks – especially electric-powered ones – would be more efficient and cleaner.

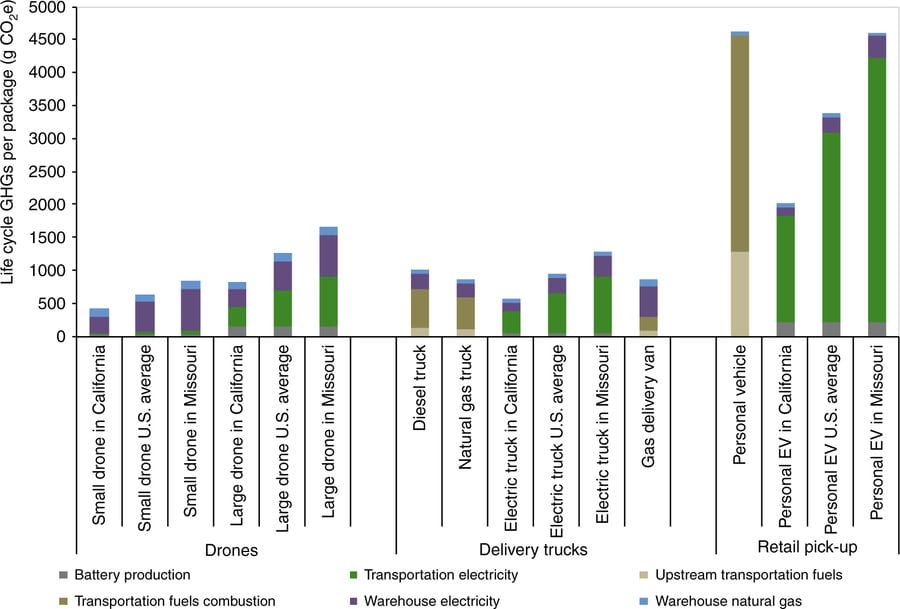

Comparison of life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions per package delivered for drone and ground vehicle pathways under base case assumptions | Credit: Nature.com

According to research, electric power generation in the U.S. is gradually becoming cleaner; in order to illustrate the range of energy needs and environmental effects they focussed their attention on California, which has a low-carbon grid, and Missouri, which is in a carbon-intensive region. After combining all the factors, the researchers found that package delivery with small drones can be better for the environment than delivery with trucks or vans.

The resulting figures differed from region to region, but overall it was found that small drones were better than any truck or van, whether powered by diesel fuel, gasoline, natural gas or even electricity. On average in the U.S., truck delivery of a package results in about 1 kg of greenhouse gas emissions. In California, drone delivery of a small package would result in about 0.42 kg of greenhouse gas emissions – a saving of 54 percent from the 0.92 kg of greenhouse gases associated with a package delivered by truck in that state; while in Missouri the improvement would be smaller – just a 23 percent reduction – but nevertheless an improvement.

The findings regarding larger drones were less substantial – while they were 9 percent better than than diesel trucks when in California, but less impressive when charged in Missouri; this might be because large drones need more kilowatt-hours to fly a mile, thus the carbon intensity of electricity is more significant for large drones.

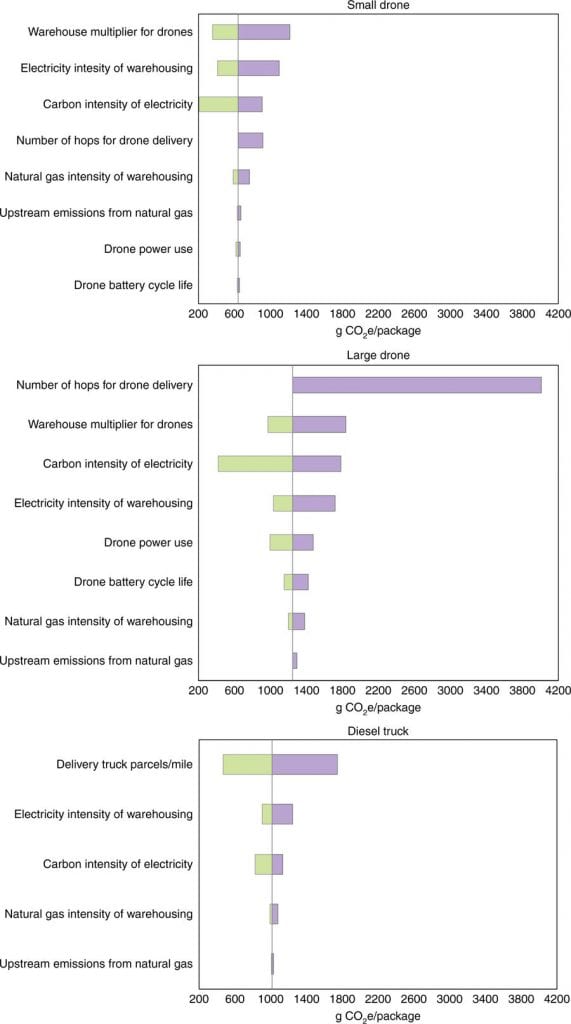

Greenhouse gas emissions per package delivered for the quadcopter, octocopter, and diesel truck. Vertical lines mark the base case result for each mode. Green bars show the decrease in emissions and purple bars show the increase in emissions given parameters | Credit: Nature.com

The team believe that in areas where energy is typically generated from clean sources, it is nevertheless probably a better option to deliver larger packages via electric vans or electric trucks rather than large drones, because of the extra warehouse energy needed for drones.

They suggest the best ways to improve the efficiency of ground delivery vehicles, might involve increasing the number of packages delivered per mile or switching to electric delivery trucks or vans.

The researchers say as with all energy models, estimates can change depending on the assumptions used and the amount of space needed to store packages for drones, and how much energy drones use, are all important factors, as is the carbon footprint of the electricity used.

So what are the implication for the package delivery industry? As more and more people turn to online shopping, the research suggests that in order to achieve the best environmental benefits, companies should focus on using smaller drones charged with low-carbon electricity to deliver light packages, and on limiting how much warehouse space is dedicated to serving delivery drones. This may be reality sooner than you think – companies such as Workhorse are already working on systems such as these. For now, they recommend that heavier packages be delivered by energy efficient ground delivery vehicles.

The research was published in Nature.com, Nature Communications volume 9, Article number: 409 (2018), doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02411-5.