AI

Drones Count Rhinos and Gnus in Namibia

Drones Count Rhinos and Gnus in Namibia

Fast and accurate, researchers are using drones to count the animals in a wildlife sanctuary in Namibia.

At the heart of this is an image recognition software that analyzes the aerial photographs of the drones.

The challenge is considerable. Certain African national parks cover areas half the size of Switzerland, according to a statement issued by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) on Wednesday. A count of antelopes, rhinos and wildebeest is so expensive and can only be done rarely.

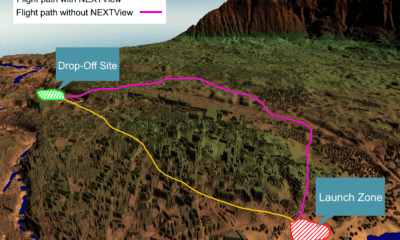

With drones, however, researchers can fly over large areas at low cost. It will shoot more than 150 images per square kilometer, which can then serve as the basis for the count.

“By automating part of the counting process, we want to make it easier to gather more accurate and up-to-date data,” Devis Tuia is quoted in the paper that initiated the project called Savmap in 2014 at the EPF Lausanne. Today, Tuia, a former professor at the University of Zurich, holds a professorship at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

To evaluate the photo material Tuia and his colleagues rely on artificial intelligence (AI), which is based on machine learning. This means that the AI has to be trained accordingly.

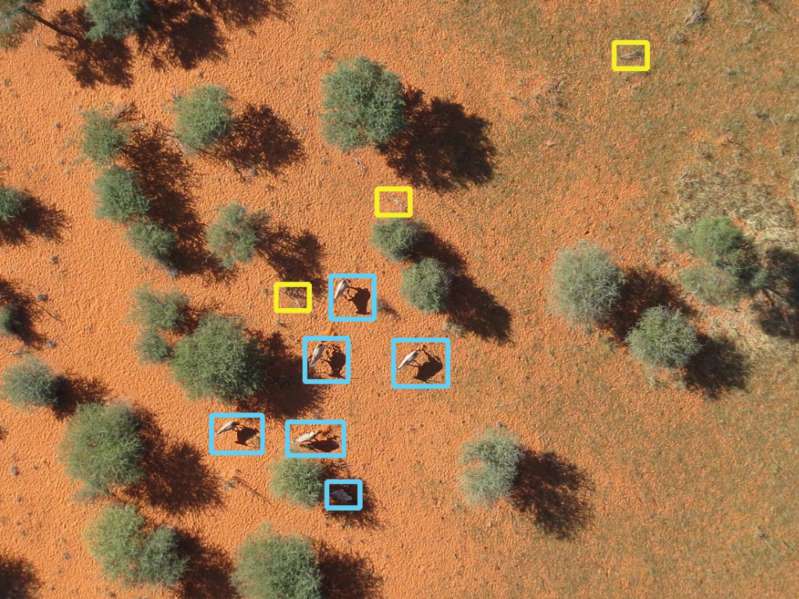

In this case, it is trained distinguish animals from shrubs and rocks. With the algorithm developed by PhD student Benjamin Kellenberger, most images without animals can be eliminated immediately. For the other photos, the program identifies objects that could be animals, as the researchers in the journal “Remote Sensing of Environment” report.

“This first phase to clean up the footage is the longest and most laborious one,” notes Tuia in the statement. According to the researcher, this work can only be done by AI if no animal is obscured. Therefore, the software must have a fairly large tolerance, even if it gives more false-positive findings.

So the team trained the AI accordingly. She received aerial photographs provided by volunteers for evaluation. When the software interpreted a bush as an animal, it received a penalty point. If she did not recognize an animal, the trigger was 80 times bigger.

When the AI cleans up the drones’ aerial photographs, a human takes over the final check. This semi-automatic method was developed in collaboration with the biologists of the Kuzikus Reserve in Namibia. Since 2014, the researchers there have been using drones from the Swiss company senseFly to fly over the reserve.

At first skeptical, Friedrich Reinhard, director of the reserve said, “The drones produce so many pictures that it seemed almost useless.”

But thanks to the AI cleanup, a single person can complete a full census of the animals in the 100-square-kilometer reserve in about a week. This is cheaper than counting by helicopter and even more accurate.