News

NASA to Send Drone to Titan

NASA to Send Drone to Titan

NASA is going to send a drone called Dragonfly to Saturn’s largest moon Titan. It is planning to launch in 2026 and land on Titan in 2034.

The Dragonfly mission falls under NASA’s New Frontiers programme, which began a selection process with 12 proposals in April 2017, and was narrowed to just two that December: Dragonfly and the Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR) mission, a plan to revisit the asteroid 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – the same one that the Rosetta spacecraft visited from 2014 to 2016 – and return a sample of its dust to Earth for further study.

Both mission teams were given $4 million to develop their concepts. Now, the Dragonfly researchers will get an additional $850 million to actually build the spacecraft, along with a rocket ride to Titan. The spacecraft has been under consideration for two-and-a-half years in NASA’s class of science missions, called New Frontiers, which are supposed to cost less than $1 billion.

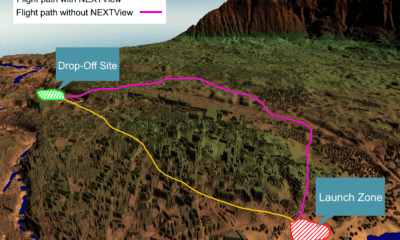

The mission will consist of a plutonium powered quadcopter 1metre high and 3 metres across. The drone will use its rotors to hop around the surface, covering far more ground than a rover could and taking valuable data from multiple distinct locations.

Making the announcement on 27 June Dragonfly team leader Elizabeth Turtle said, “These ingredients that we know are necessary for the development of life as we know it are sitting on the surface of Titan, they’ve been doing chemistry experiments basically for hundreds of millions of years, and Dragonfly is designed to go pick up the results of those experiments and study them.” The mission will be developed and led from the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Laurel, Md.

NASA said in a statement: “During its 2.7-year baseline mission, Dragonfly will explore diverse environments from organic dunes to the floor of an impact crater where liquid water and complex organic materials key to life once existed together for possibly tens of thousands of years. Its instruments will study how far prebiotic chemistry may have progressed. They also will investigate the moon’s atmospheric and surface properties and its subsurface ocean and liquid reservoirs.Additionally, instruments will search for chemical evidence of past or extant life.”

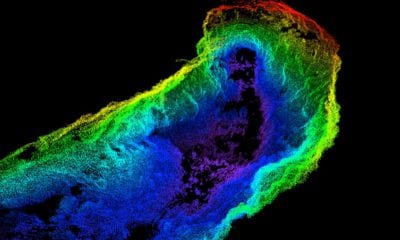

The craft will land first at the equatorial Shangri-La dune; exploring the region in short trips before building up to longer leapfrog flights of 8km. Dragonfly will study the atmosphere as it flies around, and touchdown for extended stays on the moon’s surface. The drone will explore areas where methane- and ethane-rich lakes recently dried up — and in the process, might have left behind residue rich with organic compounds like those that may have existed on early Earth before life arose. The hope is the lander will eventually fly more than 175km.

“Titan has all of the key ingredients needed for life,” says Lori Glaze, head of NASA’s planetary sciences division.

Titan’s atmosphere is composed of nitrogen, like Earth’s, but is four times denser. Its clouds and rains are methane. The second-largest moon in the solar system, Titan has a thick water ice crust, beneath which is an ocean made primarily of water.

The underground ocean could harbour life as we know it, while the hydrocarbon lakes and seas on the moon’s surface could contain life forms that rely on different chemistries – or the body could be lifeless.

Titan is about 1.4 billion kilometers from the Sun, with surface temperatures of around -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-179 degrees Celsius) and surface pressure about 50 percent higher than Earth. In 2005, the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe became the first spacecraft to land on Titan. It measured the temperature, pressure, and density of Titan’s atmosphere during its descent, and sent back pictures of the rugged, rocky landscape for 72 minutes after it touched down.

If Dragonfly is successful, it could help to reveal how life arose and took hold of our planet. Those secrets could offer valuable insights into the search for life elsewhere in the universe. Bio-geochemists at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who are also working on Dragonfly craft, have reportedly developed unique experiments designed to replicate the conditions of Titan’s ocean within a series of Ping-Pong-ball-sized incubation chambers.

It’s a world utterly unlike our own, and yet “we know it has all of the ingredients that are necessary to help life form,” said Lori Glaze, NASA’s planetary science division director. Titan’s complex rings and chains of carbon are fundamental to many basic biological processes and may resemble the building blocks from which life on Earth first evolved.

That craft would have rendezvoused with the huge space rock sucked up a sample from its surface and returned it to Earth in November 2038.