Scientists Use Drones to Map Guam’s Coral Reefs

Researchers from NASA and the University of Guam have successfully mapped a large stretch the topography of coral off the coast of the western Pacific island using an unmanned aerial vehicle or drone.

While the conventional methods for survey which could help conservation efforts used earlier, would have taken divers a month- the research team took less than two weeks to study two marine habitats using a drone, to create a centimetre-resolution digital model of the reef structure in May. The team hopes that its efforts will help researchers better in tracking changes in reef structure over time.

Steve Patterson, Jarrett van den Bergh, Alan Li, and Ved Chirayath of NASA Ames Laboratory; Romina King of PICASC at UOG; and Jonas Jonsson of NASA.

One of the project’s principal investigators, Romina King, an environmental geographer at the University of Guam in Mangilao, a village on the eastern shore of the island stated, “You’d be able to get so much coverage in a small amount of time.”

According to King nearly one-third of corals in the shallow waters around the US territory have already died following bleaching events between 2013 and 2017, when warm temperatures caused corals to expel the important algae that give the coral their colour and provide them with essential nutrients. Scientists lacked detailed measurements of reef structure, so there was no baseline to identify areas where conservation efforts were working and where they had failed. Thanks to drones however, that’s changing now.

The Guam team’s UAV is a 6-rotor carbon-fibre drone costing US$15,000 and manufactured by Chinese technology company DJI. The Matrice 600 is equipped with GPS sensors, hard drives, a memory card, a $90,000 RGB ‘fluid cam’ that corrects the distortion caused by the surface of the water to photograph beneath the waves, and a 7-colour ultraviolet sensor for testing NASA coral-identification technology. Including batteries, the assembly weighs about 12 kilograms.

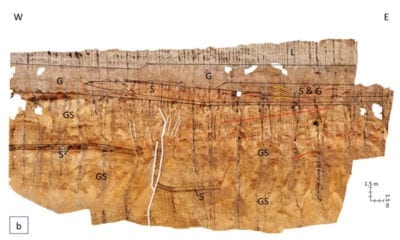

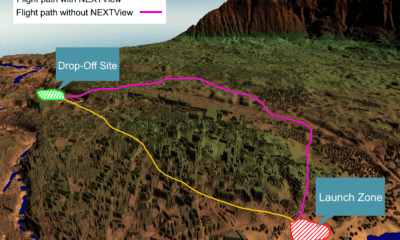

The team sent the UAV on short hops from the shore to pre-set coordinates 30.5 metres above Guam’s Tumon Bay and Tepungan Bay reefs. In total, the researchers collected about 11 terabytes of data across roughly 5 square kilometres, including image files and flight parameters such as speed, altitude and spatial orientation. NASA is using a supercomputer to process and stitch those data into 3D models of the reefs — a process that could take six months.

Ved Chirayath, who developed some of the UAV’s imaging technologies and is an Earth scientist at Stanford University, California, says he chose the Matrice 600 for its ruggedness- if one of the six batteries or rotors dies, it can still fly. In fact, when the power levels of two batteries unexpectedly dropped mid-flight and the drone had to make an emergency landing in shallow water, the team had to ship in a backup from California to complete its work. “Field work is hard, UAVs fail, instruments die,” Chirayath says. And then there’s the human element: “There’s nothing that makes [you] more seasick than staring at a drone screen on boat.”

UAVs are gaining popularity with hobbyists and among Earth scientists as well, as per King. In May, meteorologists in the United States began launching drones to study intense rotating thunderstorms called supercells across the Great Plains.