Boeing Cargo Drone Carries Massive 225 Kilograms

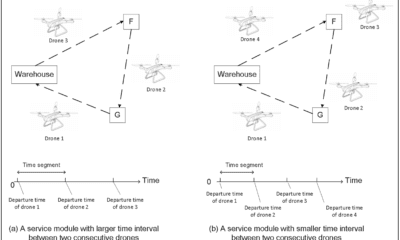

Boeing’s autonomy technology for future aerospace vehicles will be put to test with the launch of its new unmanned electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing (eVTOL) cargo air vehicle (CAV) prototype. It is designed to transport a payload up to 500 pounds for possible future cargo and logistics applications. Measuring 15 feet wide and 18 long, the Cargo Air Vehicle represents Boeing’s next step in its quest for next-generation vertical-takeoff-and-landing drones.

A team of engineers and technicians across the company designed and built the CAV prototype in less than three months. It successfully completed initial flight tests at Boeing Research & Technology’s Collaborative Autonomous Systems Laboratory in Missouri. Boeing researchers will use the prototype as a flying test bed to mature the building blocks of autonomous technology for future applications. Boeing HorizonX, with its partners in Boeing Research & Technology, led the development of the CAV prototype, which complements the eVTOL passenger air vehicle prototype aircraft in development by Aurora Flight Sciences, a company acquired by Boeing late last year. “This flying cargo air vehicle represents another major step in our Boeing eVTOL strategy,” said Boeing chief technology officer Greg Hyslop in a statement. “We have an opportunity to really change air travel and transport, and we’ll look back on this day as a major step in that journey.”

Powered by an environmentally-friendly electric propulsion system, the CAV prototype is outfitted with eight rotors allowing for vertical flight. It measures 4 feet tall (1.22 meters), and weighs 747 pounds (339 kilograms).

“Our new CAV prototype builds on Boeing’s existing unmanned systems capabilities and presents new possibilities for autonomous cargo delivery, logistics and other transportation applications,” said Steve Nordlund, Boeing HorizonX vice president. “The safe integration of unmanned aerial systems is vital to unlocking their full potential. Boeing has an unmatched track record, regulatory know-how and systematic approach to deliver solutions that will shape the future of autonomous flight.”

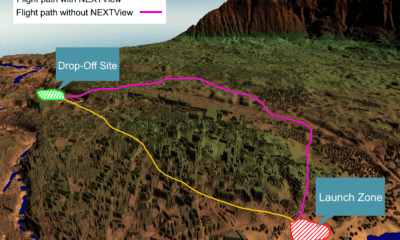

The U.S. military, of course, has a growing interest in unmanned cargo delivery. Sending expensive military helicopters on dangerous resupply missions, even when they aren’t manned, isn’t the best solution if the cargo to be delivered is relatively small. That’s precisely where next-generation delivery drone designs come in. The CAV’s virtue isn’t raw strength; its 500-pound payload is one-twelfth that of the K-Max. Also, the computers on older helicopters can’t handle some of the more interesting elevation data that can be used to better guide autonomous aircraft. “We have elevation data that’s more precise” than the set used by older helicopters like the Apache, sometimes abbreviated DTED, Matt Baldwin said at a 2016 Defense Oneevent on future helicopters. That’s one reason why the future of unmanned rotary-wing airlift is new designs, not retrofitted older aircraft. It’s also one more reason why future delivery drones likely won’t look like what’s touching down today.