Using Unmanned Systems to Better Understand Australia’s Dugong Populations

Dugongs, rare and elusive creatures that they are, are fascinating creatures that have had some suggesting they are the inspiration for mermaids.

Their gentle nature, tendency to eat only a small range of sea plants growing in shallow warm waters and give birth only about once every five years means that they are at risk, and with declining populations are listed as either endangered or vulnerable according to varying state listings.

Known in scientific circles as ‘marine megafauna’, the dugongs of the Western Australia Pilbara region are now being studied by researchers from Murdoch University, using drones.

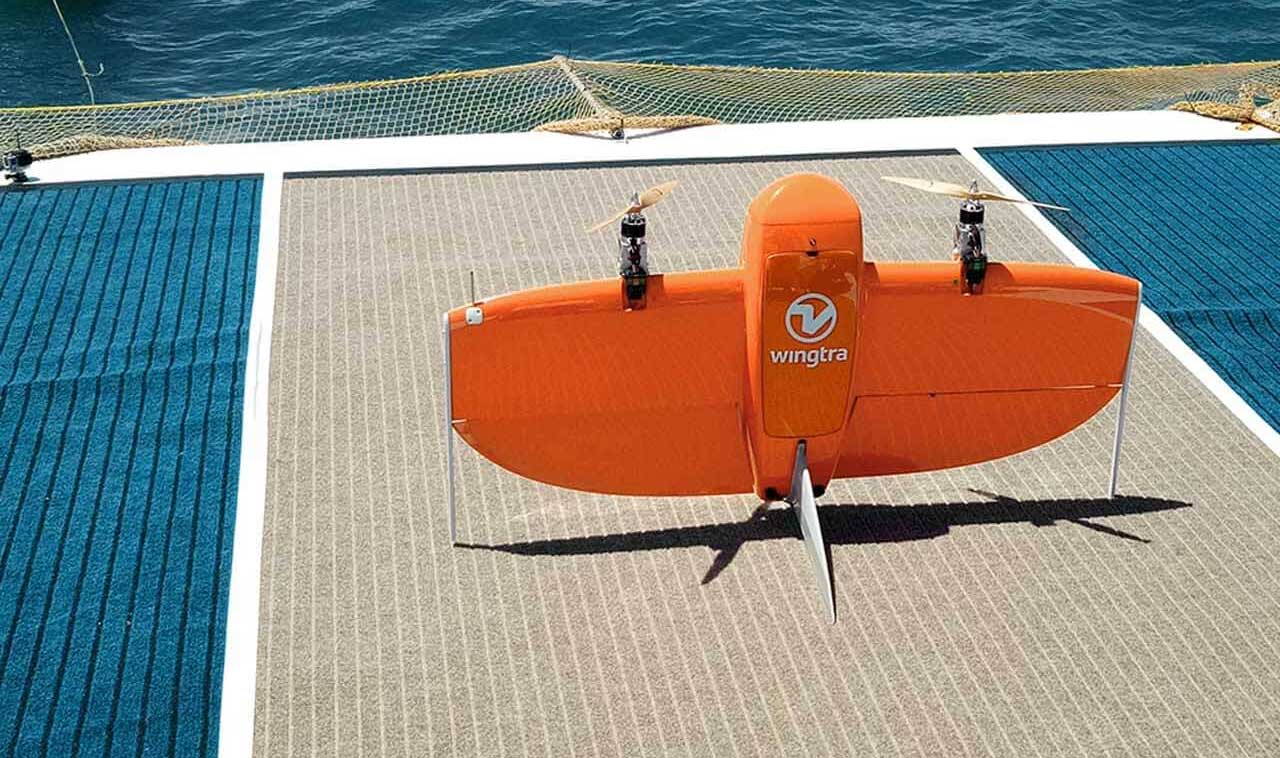

On a three week trip conducted recently by postDoc research fellow Dr Christophe Cleguer and his team (including MUCRU member Dr Julian Tyne), methods for using two very different types of drones were developed to rapidly survey the local dugong population – a DJI Phantom Pro quadcopter and a WingtraOne fixed wing VTOL drone.

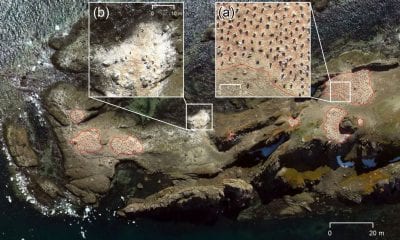

Source: MUCRU

The work forms part of a project funded by both the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) and MU and also involves seagrass specialists hailing from WA’s Edith Cowan University.

We spoke with Dr Cleguer to understand more about the drones and what it all means for the future of dugong and other animal research.

What got you interested in using UAVs to enhance your research?

Aerial surveys have been used for more than two decades to monitor dugong populations. They have traditionally been conducted by teams of observers on board small planes. But these surveys are potentially dangerous (11 people have died from marine mammal aerial surveys!). While aerial surveys allow us to survey large areas (e.g. over 100s of square kilometres) and to estimate population sizes and the distribution of our target species, they are not practical for conducting frequent and rapid local-scale surveys (e.g. in a small bay or area of interest that is only 10s of square kilometres). The resolution of the data collected from those surveys is also too low to get an understanding of the animals’ habitat use at a fine scale.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) offer a safer alternative to aerial surveys and they provide more accurate data. Depending on the scale and intensity of the survey, UAVs can also be a very cost-effective way to collect information about dugongs!

What was behind your choice of the Phantom and the Wingtra drones?

One of our current researches focuses on testing and developing UAV-based methods that will provide information about dugongs at a range of spatial scales. The WingtraOne and P4Pro have the potential to do that but at different spatial scales.

The WingtraOne is a user-friendly mid-size hybrid vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) recovery system. So, this tail-standing fixed-wing aircraft can take off and land vertically and transition to horizontal mode for surveying. This is a key asset for us because our operations are restricted to the small deck of a boat. The high flight endurance (up to 45min), range (up to 10km), and sensor capabilities of the WingtraOne (our drone is equipped with the high end Sony RX1RII digital camera) also enable us to collect data over a large area while retaining the image quality we need to detect dugongs.

We are also testing and developing methods with the P4Pro because it is a more affordable and commonly used off-the-shelf UAV but the area we can cover with this system is much smaller.

What kind of sensors are you using to collect data? (cameras, thermal sensors etc?)

At this stage the methods we are developing only require the use of digital cameras because we want to collect still images to detect dugongs during the day. But we already have ideas involving the use of thermal sensors for future research projects.

What has the learning curve been like to get the most out of the drone data? Wins, challenges?

Developing UAV-based methods to survey marine megafauna is a long and steep learning curve, as opposed to what many people can think! It isn’t just about getting whichever drone and go out there to collect dugong images, unfortunately there is a lot more to it!

A whole suite of tests had to be conducted to get to where we are now, including (but not limited to):

- Conducting a systematic review and performance analysis of candidate UAVs to choose which system will be the most adequate to help us answer our research questions.

- Investigating the technological and environmental factors affecting detection rates of marine fauna in still images (check out this paper for more information: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0079556 ).

- Comparing the detection rates of marine fauna from human observers on manned aircraft versus still images captured from the UAV (article in prep).

- Developing new methods to survey dugongs at a range of scales using UAVs and ensuring that the resulting data can be compared to the data that used to be/is collected from manned surveys.

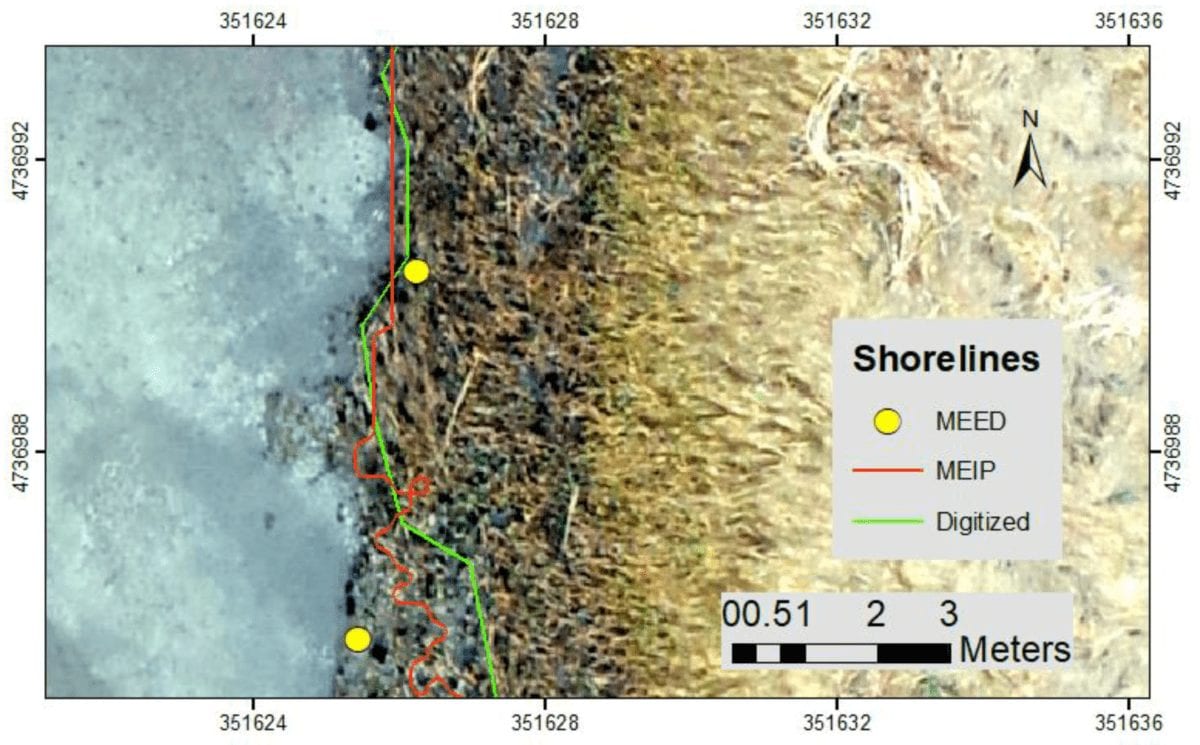

- Developing methods to process the images from UAV surveys (our team has developed an automated detection algorithm, using machine learning, or neural networks, which so far is trained to detect dugongs).

Your team used an algorithm to ‘see’ the dugongs, can you see this translating to other animals?

Absolutely! And we are working towards that already.

Any preliminary findings you can share about the dugongs?

Well what I can say from my recent fieldtrip in the Pilbara (Western Australia) for now is that we are now able to survey local areas of up to 50km2 and to process the data to obtain maps of dugong sightings and density in just a few days! This used to take weeks if not months to achieve! One of the surveys we conducted was at the bottom of Exmouth Gulf, and it confirmed that dugongs occur in large numbers in this area.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?